| Please take note: | |

| This article is a work in progress and is currently incomplete. Additional content will be added as it is written and sourced. |

Lesbian is most often defined as a woman who is attracted to other women romantically, sexually, or both, among many other definitions.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] The term is generally used as a self-identification of sexual or romantic orientation.[10] Although lesbians are frequently defined as women who are exclusively attracted to women,[2] they have also been referred to as women primarily attracted to other women.[9] Some prefer to use or additionally use "gay" or "gay woman" as an identifier.[11]

Lesbians have debated who shares their identity and is part of the lesbian community for over a century.[12] They have variously been defined based on sexual behaviors, sexual attractions, or self-identifying with the label. For instance, women who self-identify as both bisexual and lesbian[note 1] would not be included in a definition that specifies lesbians are only oriented toward women, but would be in a broader definition that encompasses other labels.[14] Definitions also vary in whether or not they use expanded language regarding gender, such as a person who self-describes as a woman[9] or phrasing that explicitly includes people who do not identify only as women, such as woman-aligned[note 2][11] and some genderqueer and/or non-binary people who feel a connection to womanhood.[15]

Lesbians may be cisgender or transgender;[2][16][17] since gender is a separate concept from sexual orientation, someone may be both trans and lesbian.[note 3][2][16] Based upon their assigned gender at birth and attraction to women, and prior to realizing their gender identity and transitioning, some trans women (assigned male at birth) formerly identify as straight and some trans men (assigned female at birth) as lesbian. Trans women attracted to women may subsequently understand themselves as lesbian women. As lesbian communities tend to be more accepting of masculine and gender non-conforming people who were assigned female at birth than straight communities, trans men often initially identify as lesbians before transitioning; however, this does not mean that all butch or otherwise masculine lesbians are transgender. Depending on individual circumstances, some trans men maintain their lesbian identities and community involvement as men.[18]

Certain lesbians have used the label to describe their gender in addition to their attractions.[19] In the Gender Census, an annual online international survey of people who do not strictly identify with the gender binary, participants indicated their personal identifiers; the item "lesbian (partially or completely in relation to gender)" was selected by 12.9% of the participants in 2021[20] and 13.8% in 2022.[21]

Etymology

Painted vase depicting Sappho (c. 510 BC)

The term "Lesbian" originally referred to people or things from the Greek island of Lesbos. It is associated with famous poet Sappho, a community leader from the island of Lesbos who wrote multiple love poems to other women circa 600 BCE.[6] The adjective "sapphic" is also derived from Sappho.[22] Sappho also wrote erotic and romantic verses that included men, but in English language texts, her particular association with the erotic love between women has been dated to 1732 or before. By 1870, "lesbianism" had become a noun for a woman's erotic interest in other women or homosexual relations between them,[23] while the phrase "lesbian love" was in use by 1883, originally circulating in U.S. medical journals that framed sexual intimacy between women as pathological.[24] Previously used as an adjective related to the isle of Lesbos or to amatory poetry, "lesbian" has been in continuous use since 1890[23] to describe romantic and/or sexual behavior between women regardless of their specific sexualities, such as "lesbian couple", "lesbian sex", or "lesbian kiss".[6] By 1904, lesbian was in use as a noun.[25]

Community

History

During the Weimar Republic (1919–1933)

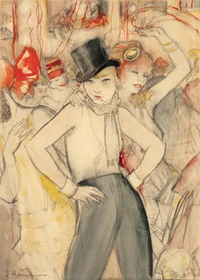

Sie repräsentiert! ("She represents!") by Jeanne Mammen, c. 1928, depicts a party in a lesbian bar.

In Germany, the word "homosexual" was widely used, but not universally loved, by gay men and lesbians by the 1920s. Other language used by homosexual women included lesbianer (lesbian), freundin (female form of "friend"), and tribade (from the French usage, but rare by the 1920s), along with references to Sappho. Words implying certain roles also emerged. Although less language specified feminine lesbians, Mädi or Dame were sometimes used. Lesbian magazines sometimes described "Don Juans" and the "Ben Hur type", while two words that suggested a masculine appearance, and might be loosely translated as "butch" today, were Bubi (lad, also a reference to the popular bobbed haircut) and garçonne.[12] Garçonne was derived from the French word garçon ("boy") with a feminine suffix added. Its closest English translation would be "tomboy". Victor Margueritte's 1922 novel La Garçonne, translated for English readers as "The Bachelor Girl", led to popular use of garçonne as a description for flappers, women who wore masculine clothing, and lesbians. A lesbian magazine originally published as Frauenliebe ("Woman Love") was retitled Garçonne from 1930 to 1932, and a lesbian club of that name was opened in 1931 by Susi Wannowsky.[26]

The most common Weimar era alternative to "homosexual" was "friend", placing an emphasis on emotional relationships while also obscuring the sexual element for those not in the know. Men's and women's "friendship" magazines demonstrated that a sense of shared identity was developing between gay men and lesbians, along with discussions of how solidarity would be needed for a political movement. Compared to gay men, women seemed more tolerant of androgyny and crossing gender lines, but some publications debated the traits of masculine lesbians versus feminine lesbians.[12]

After World War I, the number of lesbian cafés and clubs in Berlin increased dramatically, reaching more than fifty by the mid-1920s. Some establishments were class-segregated; for instance, the Club Monbijou West required an invitation, and the Pyramid was for celebrities and artists. The Chez Ma Belle Sœur was regarded by locals as a showplace for tourists. Other parts of the Weimar lesbian scene brought together women of various social classes that had been isolated from each other prior to the war.[12]

During the Nazi regime (1933–1945)

- Main article: Lesbian history during the Nazi regime

The history of lesbians during the Nazi regime is still being researched and compiled decades later. The experiences of lesbians and women accused of being lesbians are difficult to trace and cross-reference across scattered documents. Few women were identified as lesbians in official records kept during the Nazi era. Victims were not necessarily lesbians despite being documented as such by the Nazis; it is unclear how many of the allegations were false.[27]

Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime used a strengthened version of Paragraph 175, which criminalized male homosexuality, to engage in extensive, systematic persecution of gay men.[27] Sexual intimacy between women was not criminalized, with the exception of Austria, but the Nazis disrupted informal gay and lesbian social networks, raided and closed their public meeting places, and put locations under surveillance. While some fled the country, others attempted to outwardly conform by entering marriages of convenience, sometimes between a gay man and a lesbian. The Third Reich saw marriage and motherhood as the ultimate purpose of women, specifically to increase the "desirable" Aryan population. To the Nazis, lesbians could be "cured"[28] to bear Aryan children by persuasion or by force.[27][28]

Lesbians did not experience the same systematic persecution as gay men, but they could be investigated, arrested, and sent to prisons or concentration camps for other "offenses", such as being Jewish or engaging in subversive political behavior; their sexuality was not the official reason listed. While gay men were forced to wear a downward-pointing pink triangle in camps that used coded badges, lesbians were instead marked with whichever badge corresponded to their official reason for arrest and internment.[27] Some lesbians were marked as "asocials" and wore a downward-pointing black triangle.[28] The black triangle has been used by some lesbians in a manner similar to how some people in the gay community have reclaimed the pink triangle as a defiant symbol.[29]

Legal challenges to lesbian literature

Dottie is pretty and stout, with long, fluffy black hair, black eyes. She always wears sleeveless gowns, while Sammie 'struts' her tightly fitting tailored suit, and the inevitable attached collar and tie, which means so much in the life of a Lesbian. The two often get publicity in current periodicals and are generally called 'husband and wife.'

Sammie smiles when she reads these articles, while Dottie silently blushes.

This 'Flowery Tea Pot' has become a very popular and interesting rendezvous for loving couples of the same sex, mostly the fair sex . . . where over a cup of tea lovers meet and wistfully look into each other's eyes . . . where new ones and lonely ones get acquainted and embrace each other, swaying to the melody of a dreamy waltz.Eve Adams (as "Evelyn Addams"), Lesbian Love (1925)

Chawa Zloczewer was a Polish Jewish lesbian who is best known as Eve Adams, the name she eventually adopted in the United States. The U.S. government first began surveillance of her based on "radical activities", primarily selling subscriptions to leftist magazines. She established "Eve's Hangout" in New York's Greenwich Village, a tearoom that attracted fellow lesbians and gay men. In February 1925, she wrote a short book called Lesbian Love as "Evelyn Addams". It included fictionalized versions of Adams and other lesbians she knew, as well as drawings of pairs of clothed and nude women, loving each other. It reflected beliefs at the time about lesbians as born "sexually inverted", or having a masculine nature, and pairing off with feminine women. Only 150 copies were made for private distribution.[24]

Nevertheless, after an undercover policewoman entrapped Adams, she was found guilty of publishing an "indecent book" and sentenced to the maximum one-year imprisonment. Adams asserted that her book was "not in any way immoral, indecent, or vulgar." Some contemporary reports sensationalized her arrest and trials. After release from prison, the federal government held the deportation hearings they had previously organized against her, and she was deported to Poland. She eventually moved to Paris. In December 1943, she was arrested in Nazi-occupied France and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. She died sometime between then and the liberation of the camp in 1945.[24]

In 1928, British author Radclyffe Hall published The Well of Loneliness, a semi-autobiographical novel about "sexual inversion" like hers. Its depiction of a lesbian relationship led to attacks in the press and withdrawing it from publication in the Britain. Her publisher was charged under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857. Finding the book obscene and capable of corrupting readers, the court ordered it removed from circulation and destroyed. The labeling of the book as "obscene" drew attention of publishers in the U.S., and the firm that bought the U.S. rights hired a lawyer who successfully defended it in 1929.[30]

Women's Barracks, by Tereska Torrès, was published in 1950 by Gold Medal Books and is regarded as the first lesbian pulp novel.[31] The semi-autobiographical novel was based upon the diaries she kept as a member of the Free French Forces during World War II, novelized and published at the urging of her husband. Multiple lesbian women are described and identified as such in the story, while other women engage in occasional liaisons and are not regarded as "real Lesbians".[32] Torrès did not regard it as a "lesbian" novel, merely one that included sexuality in a way that Americans were not accustomed to, and she was not a lesbian herself. Women's Barracks became the first bestselling paperback original novel, selling two million copies in just its first five years. It was also subjected to a United States congressional committee on "current pornographic materials" that eventually allowed it to remain uncensored because it had "moral lessons" about the so-called "problem" of lesbianism; however, a Canadian court review ruled it obscene.[33]

Mid-20th century, United States

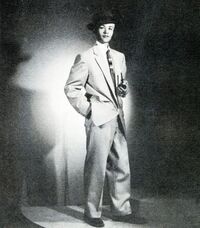

A butch/femme couple photographed in front of their apartment in the 1950s

In the 1940s, lesbian group solidarity began to grow in the United States, and the 1950s built on that through night life at lesbian bars and house parties. In the U.S., participation in lesbian communities was largely predicated on adopting butch/femme culture and its associated roles as they were understood in that time period. The butch/femme code of personal behavior became a social imperative to increase the visibility of lesbians to the public and to each other, particularly with the expression of butch identities, whether or not a femme partner was present.[34]

Locations where lesbians congregated became sites of resistance and defiance of the societal repression of women's sexuality. Growing lesbian pride and solidarity developed into the political consciousness of gay liberation that spread with the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the subsequent decades. Bar culture in particular evolved into politics focused on the right to congregate rather than the homophile movement that focused on the right to equal protection.[34]

Stonewall riots

It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil rights disobedience—it wasn't no damn riot.

In the late 1960s, it was illegal in the state of New York for people considered "of the same sex" to publicly hold hands, kiss, or dance with each other.[35] Police also harassed and arrested people who were not wearing attire that matched binary genders imposed by the police, such as those the police viewed as "female" who was not wearing enough "feminine" attire. Lesbians and trans men were targeted on the streets and in bars for harassment, assaults, and examinations of their anatomy; for instance, the drag king Rusty Brown was repeatedly arrested for wearing a shirt and pants.[36]

The Stonewall riots, also called the Stonewall uprising,[37] started on June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, a gay club located in Greenwich Village in New York City. Initially a confrontation between patrons and police officers, it was strengthened by other members of the LGBTQIA+ community and neighborhood street people.[36] Despite several drawbacks, the Stonewall Inn was an important institution for the local community. The Genovese crime family, a Mafia organization, found it profitable to control most of the gay bars in Greenwich Village, including Stonewall Inn. Police officers were bribed to ignore the bar or tip it off prior to the frequent police raids,[35] which usually resulted in people who were inside the bar fleeing and those outside dispersing.[37]

Stormé DeLarverie, sometime between 1955 and 1969

In the early morning hours on June 28, 1969, Stonewall Inn was not tipped off before police officers arrived with a warrant. The officers were physically aggressive with the patrons and began arresting employees for liquor license violations and patrons for "cross-dressing".[35] Stormé DeLarverie, who worked as a drag king, and several fellow butch lesbians attempted to defend their friends, but were beaten by police.[38] Although there is some debate about whether or not DeLarverie was the party in certain events, along with the sequence of those events,[38][39] she has been attributed with throwing the first punch and initiating the riot. At some point, DeLarverie stated an officer told her to move along, called her a slur referring to a gay man, and hit her; she punched back.[39] When a lesbian was forced into the police van and struck over the head, she shouted at the onlookers to act; the crowd began throwing objects at the police.[35] Some accounts are that DeLarverie complained about her handcuffs and was struck with a baton. She was dragged into the police wagon and attempted to flee toward Stonewall Inn. When she was pulled back and further beaten by the officers, she reportedly yelled to the crowd, "Why don't you do something?"[38]

Over the following six days, the community engaged in protests and violent clashes with law enforcement on Christopher Street, in neighboring streets, and in nearby Christopher Park.[35] Although the uncoordinated actions are often called a riot, DeLarverie described it as a rebellion, uprising, and civil rights disobedience.[38] The event is widely regarded as a catalyst for the civil rights movement for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in the United States.[40]

Lesbian-feminism and the lesbian sex wars

Lesbian-feminism[note 4] and the lesbian separatist movement emerged from within the larger Second Wave of feminism, which had largely ignored and excluded lesbians.[41] Many radical feminists believed the sexual revolution of the 1960s was more exploitative than liberating and saw sexual liberation and women's liberation as mutually exclusive. They wanted feminists to stop focusing on sex, and some viewed lesbians as "hypersexual".[42] In 1969, the president of the National Organization of Women (NOW), Betty Friedan, said that lesbians were the "lavender menace" to the reputation of the women's liberation movement (Susan Brownmiller further dismissed lesbians as only an inconsequential "lavender herring" in a March 1970 article in The New York Times).[43] Author and lesbian Rita Mae Brown was relieved of her duties as editor of New York-NOW's newsletter; in response, she and two other lesbians resigned from other NOW offices and issued a statement about homophobia within NOW. In late 1969, Brown joined others in organizing a lesbian-feminist movement.[42] At the Second Congress to Unite Women on May 1, 1970, the Lavender Menace—a group of lesbian activists from Radicalesbians, the Gay Liberation Front, and other feminist groups—coordinated a demonstration to successfully demand recognition of lesbianism and the oppression of lesbians as legitimate feminist concerns.[43] Those planning the action included Brown, Ellen Bedoz, Cynthia Funk, Lois Hart, and March Hoffman.[42]

The Radicalesbians additionally distributed their article "The Woman Identified Woman", which framed "homosexuality" and "heterosexuality" as categories created and used by a male-dominated society to separate women from each other and dominate them. The article argued that since lesbianism involved women relating to women, it was essential to women's liberation. They called for complete separatism from men.[41] According to "Lavender Menace" member Jennifer Woodul, the term "woman-identified" may have been proposed by Cynthia Funk, and it was meant to be less threatening to heterosexual women than "lesbian". The group criticized characterizing lesbians based on sexuality as "divisive and sexist", and redefined lesbianism as a primarily political choice that showed solidarity between women.[42]

Expressions of lesbian sexuality were often treated as problematic by the lesbian-feminist movement,[34] and the acceptance of lesbians in the feminist movement was contingent upon de-emphasizing sexuality. Many heterosexual feminists did not welcome discussions of any sexuality whatsoever and thought feminism should move away from the topic; thus, lesbian-feminists further reframed lesbianism as a matter of sensuality rather than sexuality. They also portrayed men's sexuality as always aggressive and seeking to conquer while women were portrayed as nurturing and seeking to communicate. In this ideology, lesbianism became the ultimate expression of feminism by not involving men, while sex with men was oppressive and corrupt. With men, maleness, masculine roles, and the patriarchy all seen as linked together, lesbian-feminists viewed feminists who continued to associate with men, especially by having sex with them, as inferior and consorting with "the enemy". All-"lesbian" retreats were held, and houses and communes were formed, for those seeking to practice lesbian separatism. Since any desire for men was seen as "male identified" rather than "woman identified", straight feminists were seen as unwilling or unable to commit to other women, making them lesser feminists than political lesbians who chose women.[42]

Two key texts to the lesbian-feminist movement were Adrienne Rich's[note 5] 1980 article "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence" and Lillian Faderman's 1981 book Surpassing the Love of Men. The texts emphasized loving and passionate relationships between women that were not necessarily sexual; however, they also treated sexuality as unimportant. Faderman's book claimed that the medical establishment's view of love between women as pathological led to the patriarchy treating any close relationships as suspicious and sexual; therefore, women's relationships should defy that view by no longer emphasizing sexuality. Rich continued the framing of lesbians as a political identity, a resistance to patriarchy, and commonality between all women-identified "passionate friends", warriors, and activists. She furthered the argument that being a lesbian was a choice, and that all feminists should make that choice as they removed themselves from male influences. Faderman and Rich's texts also split lesbian history from the history of gay men.[34]

The "sex wars" shifted near the end of the 1970s to encompass additional sexual expressions beyond lesbianism. Anti-pornography feminism developed in part from lesbian-feminist thoughts about straight men as inherently aggressive toward women and heterosexual sex as equivalent to violence. Butch/femme culture was seen by lesbian-feminists and anti-pornography feminists alike[44] as only an imitation of heterosexuality that reproduced the patriarchy, rather than its own rich culture. Since butch lesbians were associated with masculine traits, lesbian-feminists saw them as inherently suspicious. The free expressions of sexual desire between femmes and butches were regarded as incompatible with the lesbian-feminists' desexualized version of who could be a lesbian. Further, the importance of butches, femmes, and their culture was dismissed. When mentioned at all, lesbian-feminists treated them as if they were only a footnote, rather than presenting butches and femmes as essential to lesbian history.[34] As "pro-sex" feminists discussed sexuality, Esther Newton was one of the proponents of butch/femme dynamics. Many lesbians pointed out that the roles had transgressive potential for subverting heterosexual gender norms, rather than imitating them.[44]

Second Wave feminism's focus primarily on the concerns of white, middle-class women pushed out working-class and black women. The lesbian-feminist disapproval of butches and femmes may have derived from this classism and racism, as black lesbian culture and white working-class lesbian culture were often organized around butch/femme roles. Many black lesbian-feminists broke away to form their own groups. They had been condemned by white lesbian-feminists for fighting alongside black men for freedom, yet faced sexism within black freedom movements. Formed in 1975, the Combahee River Collective is now one of the best-known black lesbian-feminist groups.[41]

Various lesbian-feminists refused to accept transgender women as women and based their definition of "women" on genitals present at birth. When Beth Elliott, a transsexual lesbian folk singer, had her membership revoked from the Daughters of Bilitis organization in December 1972, several members resigned in protest. She was on the organizing committee for the West Coast Lesbian Feminist Conference held in 1973 and was scheduled to perform her music. When a group leafleted the conference to protest and misgender Elliott, keynote speaker Robin Morgan rewrote her speech to address the controversy, but only included transphobic rhetoric and attacks on Elliott. Over two-thirds of the attendees voted to allow Elliott to remain, but the hateful ideas in Morgan's speech spread throughout the mid-1970s.[45] Mary Daly, Sheila Jeffreys, and Janice G. Raymond also became prominent anti-trans voices. Raymond cited Adrienne Rich in a chapter called "Sappho by Surgery" in a book[46] that was published in 1979. Other lesbian-feminists broke ties with the anti-trans elements and supported trans inclusion; these included Candy Coleman, Jeanne Córdova, Deborah Feinbloom, and the Reverend Freda Smith.[45]

Flag

Double Venus flags

A double Venus flag

The Venus symbol (♀) originated as an ancient Roman astrological symbol for the female (sometimes called "the mirror of Venus"). It has since become an astronomical symbol of the planet Venus and a botanical and zoological symbol of femaleness. Two interlocking Venus symbols (such as ⚢) often represent lesbianism.[47] Multiple Pride flags combine the double Venus symbol with Gilbert Baker's rainbow designs.[48]

Labrys lesbian flag

The labrys lesbian flag

The labrys symbol was adopted as one of empowerment for lesbian feminists in the 1970s. In 1999, graphic designer Sean Campbell, a cisgender gay man, created the labrys lesbian flag for the June 2000 Pride issue of Gay and Lesbian Times magazine. His flag design superimposed a white labrys over the downward-pointed black triangle on a violet-hued background;[29] violet flowers have a long association with lesbians due to inclusion in Sappho's poetry.[49]

Some controversy arose around this flag design, however, as the black triangle is associated with the Holocaust, specifically a mark that "asocials" (including some lesbians) and other victims were forced to wear in the Nazi concentration camps.[29][49] Additionally, the labrys has been used as a symbol by some fascist organizations.[50] In the years since the flag was created, some trans exclusionists have also adopted the labrys symbol as their own,[49][50] which has led to a widespread perception of the flag as not trans inclusive.[49]

Lipstick lesbian flag and stripes

Design progression from the "Cougar Pride Flag" by Fausto Fernós, to the plagiarized "The Official Lipstick Lesbian Flag" by Natalie McCray, to the stripes-only "pink flag"

In 2008, a "Cougar Pride Flag" was designed by Fausto Fernós,[51] a drag queen who created it to be tongue-in-cheek; the intention was "to draw attention to the ongoing issue of ageism and sexism in women's sexuality".[52] It includes a semi-transparent, dark red lipstick kiss mark in the top left corner and seven stripes in shades of red and pink.[51] In 2010, the blogger Natalie McCray from This Lesbian Life[53] plagiarized Fernós' design[50][52] and presented it as her own creation that she called the "official" lipstick lesbian flag. The lipstick graphic was flattened into a solid bright pink with white highlights, and the stripes were lightened and color-shifted with a central white stripe.[53]

While McCray's image has not been widely adopted in the manner she presented it, a revision[29] using McCray's stripe colors and omitting the kiss mark gained more popularity. One version of this was posted in 2013 on a Tumblr blog with the username trans-wife; however, it was captioned as a lesbian flag rather than specific to lipstick lesbians.[54] A larger version of the pink stripe flag was posted in 2015 by the Pride-Flags account on DeviantArt.[55]

McCray's flag and its derivatives have been criticized when represented as a flag for all lesbians since it was created to be specific to one subculture.[50] McCray has been accused of making hateful remarks regarding butches, bisexual women, Asian women,[50][56] and trans people, including in a since-deleted blog post by Lydia when presenting her own Sappho-inspired flag design.[56] In a since-deleted post, McCray responded to Lydia and denied the accusations of racism, biphobia, and transphobia.[57] Since the "pink" flag originated as McCray's lipstick lesbian flag, it is similarly seen as not inclusive of butches and other gender non-conforming lesbians.[50]

Sappho-inspired flag

Lydia, a biracial (Mi'kmaw and white) genderqueer lesbian from Mi'kma'ki (Atlantic Canada),[58] was one of the people who raised concerns about the lipstick lesbian flag due to[56] racist posts made by its creator;[59] additional problems Lydia noted were how some people attempted to use a femme-only flag or its feminine pink-stripe derivative for all lesbians, along with using a design that was difficult to reproduce physically, did not have web-friendly colors, and had colors chosen for aesthetics rather than meaning. They decided to design a flag "for all lesbians. All lesbians are welcome to it." The colors came from "seeking some sapphic inspiration" in a poem by Sappho, which she addressed to a female lover:[56]

all the violet tiaras,

braided rosebuds, dill and

crocus twined around your young neckSappho, "I have not had one word from her"

Sappho-inspired flag designed by Lydia, with Maya Kern's color order

Lydia thus used violets, pink rosebuds, yellow crocuses, and green dill, with the following meanings:[56]

- Violet (#663399): Sapphic love[56]

- Pink (#FF6699): Fragility[56]

- Yellow (#FFCC33): Strength[56]

- Green (#66CC33): Healing[56]

The color order was originally different, but Maya Kern suggested the current order for improved harmony. Lydia has since observed that the flag has been referred to online as "the sapphic flag" and has been used as an umbrella pride flag "for all sapphic lesbian identities". They have clarified that "all lesbians" is inclusive of ace lesbians, trans lesbians, and those who have not yet pinned down an exact identity.[60]

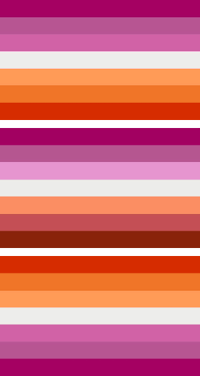

Seven-stripe pink/orange flags

From top to bottom: the primary design from shapeshifter-of-constellation's proposals, the design by nillia, and the first design posted by sadlesbeandisaster

At the end of June 2017, Mod Q of the Tumblr blog butch positivity (butchspace) posted a seven-striped orange and yellow butch flag design[61] and color meanings.[62] Days later in July, the user shapeshifter-of-constellation[note 6] posted a general lesbian flag design. The bottom three stripes use color codes sampled from the top of Mod Q's butch flag, and the top four colors were derived from those of the lipstick lesbian flag (three of them directly sampled). The stripes are visually equal in size but have slight variances upon close inspection. Alternate versions with stripes from the More Color More Pride flag were also offered. At the suggestion of Mod T from butch positivity, shapeshifter-of-constellation proposed that the white stripe could symbolize those who do not identify as butch or femme,[63] but no meanings were assigned to other individual stripes. Responding to Mod Q, they said the intention of it was a general lesbian flag for anyone in the community, not specifically a femme/butch flag.[64]

The Tumblr user Nillia made a post in April 2018 about the history of butchphobia and criticized using lipstick lesbian stripes for all lesbians; the orange butch flag was reposted as an example of "some very obscure butch designs of unknown date. Most use warm colors." Nillia's seven-striped flag design for all lesbians used the top two pink and bottom two red color codes of the lipstick lesbian flag, and a white center stripe between stripes in a new light pink and a new light orange.[65]

In June 2018, sadlesbeandisaster posted about her ideal lesbian pride flag, which she said would use the top half of the pink and the bottom half of the orange flags but orient the orange on top; she included an image matching that description.[66] The image in this post appears to be shapeshifter-of-constellation's rotated and resized.[note 7] Sadlesbeandisaster has since said she did not steal and invert shapeshifter-of-constellation's flag but rather got the idea to combine the butch and pink flags while talking with a friend and is not surprised other people had that same idea.[67] Her friend made the image for her original post, and she has maintained that it is "[her] lesbian flag design".[68] Commentary that sadlesbeandisaster was not the original designer was reblogged by shapeshifter-of-constellation in 2021.[69]

Following the first post, sadlesbeandisaster made an initial proposal of color meanings[70] before posting a version with the following meanings, from top to bottom:[71]

- Red-orange: gender non-conformity[71]

- Orange: independence[71]

- Light orange: community[71]

- White: unique relationships to womanhood[71]

- Light pink: serenity and peace[71]

- Medium pink: love and sex[71]

- Dark pink: femininity[71]

In 2019, sadlesbeandisaster posted an apology for previous comments about asexual people. She added that she would not apologize for her words regarding identifiers such as "bi lesbian", which she considers to be lesbophobic, harmful, and offensive since she defines lesbians as having no attraction to men.[72]

Community lesbian pride flag

The five-striped lesbian pride flag, also called the community lesbian pride flag

The community lesbian pride flag originated in a poll called the "Official Lesbian Flag Poll", which was posted on Tumblr[73] and Twitter on June 30, 2018.[74] By July 25, Catherine (then under the username taqwomen) had suggested a five-striped and three-striped modification of the design attributed to sadlesbeandisaster.[75] Catherine's five-striped suggestion was announced on August 28 as the poll winner.[76]

Meanings were later given to the five colors by the Tumblr user birdblinder. They are, from top to bottom:[77]

- Dark orange: transgressive womanhood[77]

- Light orange: community[77]

- White: gender non-conformity [77]

- Light pink: freedom[77]

- Dark pink: love[77]

In addition to the poll that produced the community lesbian pride flag, other polls regarding lesbian flag designs were circulated on Tumblr in 2018. The Tumblr user chiaroscura (under the username allukazaoldyeck) ran two polls that concluded by June 6, 2018, with the design credited to sadlesbeandisaster winning.[78] The which-lesbian-flag blog moderated by Cas and Niv ran a two-round survey beginning in July 2018.[79] Prior to the conclusion of the first round, they announced the removal of the pink flag derived from Natalie McCray's lipstick lesbian flag, citing the creator[80] calling an Asian woman an "anorexic freak"[59] as the primary reason.[80] After the removal, the top pick of the first round was[81] a flag design by apersnicketylemon,[82] which also emerged as the winner of the second round.[83][84]

The "Commercial Lesbian Flag Poll", which began in mid-December 2018, aimed to select a flag that could be mass-produced by Pride merchandise companies. The poll author said the reason for the poll was that the companies they reached out to required a consensus on the design. The designs included[85] were Gilbert's six-stripe rainbow flag, Lydia's Sappho lesbian flag, apersnicketylemon's flag, and taqwomen's five-striped flag. Although the poll included the seven-striped flag, the poll creator said they reached out to sadlesbeandisaster but originally did not receive permission to include it in a poll that would produce a result sold for profit.[86] After the five-striped design won, it was intentionally not called an "official" flag; the poll creator called it the "Community Lesbian Flag" to reflect the community process that led to its selection for production.[87]

The community lesbian flag has achieved mainstream recognition. By 2020, it was being produced on merchandise released by Spencer's online gift shop[88] and by Gay Pride Apparel.[89] For the Rainbow Disney Collection in 2021, Disney released an enameled Mickey Mouse head pin with the community lesbian flag stripes.[90]

Distinction

Sapphic

- Main article: Sapphic

The distinction between "sapphic" and "lesbian" depends upon which definitions are used for each word. They are often confused for each other or thought to mean the same thing, as both refer to women who are attracted to other women.[91] In contemporary usage, sapphic has become an umbrella term specifically inclusive of women with multisexual orientations (such as bisexual, pansexual, and other queer women) who may or may not be attracted to men,[91] while "lesbian" is often (but not always) defined as a woman only attracted to other women;[16][9][5] both terms are inclusive of non-binary[15] and transgender identities.[16] "Sapphic" is thus generally understood as the broader term when lesbians are defined as women who exclusively love women and when sapphics are defined as all women loving women. Different definitions of the words change that distinction.

Controversy

Defining "lesbian"

For over a century, lesbians have been debating the terms used to refer to themselves. Along with definitions created or endorsed by lesbians, others were created by non-lesbians, such as male psychiatrists and sexologists. Debates have often centered on whether a lesbian must be a woman who is exclusively attracted to and only has sex with other women. During the COVID-19 pandemic, debates continued in online communities and on social media. As of January 1, 2023, these remain daily occurrences.

Despite the importance of having a clear definition, there is still no singular definition of "lesbian", and many definitions are incompatible with each other.

20th century definitions

In Germany, during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), lesbian magazines published debates from contributors and letters to the editors regarding lesbian identity. Some argued that a woman who was married to a man or had ever had sex with a man should be excluded from the lesbian community. Others defended women who had relationships with both women and men, whether because they were self-identified bisexual women or out of pragmatic reasons related to economic needs and the contemporary social setting.[12]

Twentieth century psychoanalysts approached lesbianism as a psychological disorder that must be "cured" and turned into heterosexuality. In 1954, Frank S. Caprio published Female Homosexuality: A Psychodynamic Study of Lesbianism, which provides an overview of that perspective. While some lesbian women were described as exclusively intimate with other women and not men, he wrote, "Many lesbians are bisexual, oscillating between heterosexual and homosexual activities, and are capable of gratifying their sexual desires with either sex. Their homosexual cravings may be transitory in character." In addition, he claimed, "Many bisexual lesbians indulge in what might be called pseudo-heterosexual relations insofar as intercourse with a man tends to counterbalance their homosexual guilt. They wish to be seen with men to camouflage their homosexuality. Actually they prefer the love of their own sex." Like many other psychoanalysts, he believed lesbians were repressing their heterosexuality and only seemed "frigid" with men due to unresolved conflict, which resulted in unconscious defense mechanisms to avoid sex with men.[92]

Caprio disagreed with another author, Antonio Gandin, that lesbians could be classified as either "sapphists or tribades", instead supporting an anonymous writer's division into "predominantly mannish" and "predominantly feminine". Caprio's glossary defined lesbianism based on sexual acts, and the only kind of love mentioned was erotic. It included the following definitions:[92]

- "Bisexuality. A sexual interest in both sexes; the capacity for pleasurable relations with either sex."[92]

- "Homosexuality. Sexual relations between persons of the same sex."[92]

- "Lesbian. A female homosexual."[92]

- "Lesbianism, Lesbian Love. Female homosexuality; the erotic love of one woman for another; the relationship may consist of kissing, breast fondling, mutual masturbation, cunnilingus or tribadism."[92]

- "Sapphism. Homosexual relations between two women."[92]

- "Sapphist. One who performs cunnilingus on another woman."[92]

- "Tribade. A woman who practices tribadism."[92]

- "Tribadism. The act of one woman lying on top of another and simulating coital movements so that the friction against the clitoris brings about an orgasm."[92]

Marijane Meaker's We Walk Alone, released in 1955 under the pseudonym Ann Aldrich, is a non-fiction book presented as an insider's look into lesbians by a lesbian. She reported what psychoanalysts of the time claimed about lesbianism as a "psychological orientation that is different from the accepted social pattern", a disorder of immature and abnormal women, and she accepted Havelock Ellis' "sexual inversion" theory. However, she also asserted that society should neither condemn nor pity lesbians, simply understand them. She described several "types" of lesbians: the butch, the fem, the latent lesbian, the "one-time" lesbian, the repressed lesbian, and the bisexual lesbian (divided into the flirt and the one-night-stand adventuress).[93] Contrary to her treatment of bisexual and lesbian women as separate in her 1952 novel Spring Fire,[94] she presented bisexual women as a type of lesbian who is consistently involved with men and women rather than having a single or occasional experience with either. Her overall description of lesbians was the following:[93]

The fact of the matter is that lesbianism cannot be accurately defined, nor can the lesbian's personality traits be lumped into any category that will include all of her characteristics, and yet exclude those of the remainder of the female population. Who is the lesbian? She is many women. […] There is no stereotype in the over-all picture of the lesbian. This is the first discovery I ever made about the group of which I am a member. […] There is no definition, no formula, no pattern that will accurately characterize the female homosexual. She is any woman.

Marijane Meaker (as "Ann Aldrich"), We Walk Alone (1955)

Lorraine Hansberry, whose play A Raisin in the Sun was the first by an African American woman to open on Broadway, privately wrote of her identification as a lesbian; she was married to a man and was not "out". By 1957, she was member of the lesbian organization Daughters of Bilitis and subscriber to its magazine, The Ladder. She sent an anonymized reader letter[95] in response to prior writings in the magazine about lesbians who had husbands despite an "interest" in women. Objecting to the language, she wrote:[96]

I mean really, unless I am afflicted with the worst kind of misunderstanding, the homosexual impulse does transcend 'interest' in other women. Isn't the problem of the married lesbian woman that of an individual who finds that, despite her conscious will oft. times, she is inclined to have her most intense emotional and physical reactions directed toward other women, quite beyond any comparative thing she might have ever felt for her husband—whatever her sincere affection for him?

Lorraine Hansberry (as "L.N."), The Ladder, vol. 1, no. 11 (August 1957)

Edward Sagarin (as "Donald Webster Cory"), a gay man who spent time observing and interviewing members of the Daughters of Bilitis, wrote The Lesbian in America in 1964. He described some lesbians as exclusive lesbians who fell into the number 6 rating on the Kinsey scale (exclusive homosexuality), rather than the ratings 4 or 5 (predominantly homosexual); other non-heterosexual women were bisexual in their inclinations, activities, or both. Sagarin offered a lesbian definition that included attraction and self-identification:[97]

A lesbian is a woman who feels a strong and urgent need, usually a chronic or continuing or recurring need, to have close, intimate carnal contact with another woman, and whose drive for sexual contact with men, if it is not entirely absent or replaced by fear, disgust, horror, and repulsion, is at least very weak. A lesbian, in short, is a girl who feels that she is a lesbian, and who, whether she is happy or sad, accepting or rebelling against her condition, identifies herself as being part of that group.

Edward Sagarin (as "Donald Webster Cory"), The Lesbian in America (1964)

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, a lesbian couple who founded of the Daughters of Bilitis, published Lesbian/Woman in 1972. Their introduction began with this definition:[98]

A Lesbian is a woman whose primary erotic, psychological, emotional and social interest is in a member of her own sex, even though that interest may not be overtly expressed.

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, Lesbian/Woman (1972)

In Lilian Faderman's book Surpassing the Love of Men, she said that lesbianism had previously been defined by men as just a sexual preference or a sexual act between women. She criticized German lesbians in the early 20th century who had identified as having an inborn trait in common with male homosexuals, such as those who related to the "third sex" concept, and who considered themselves born different from heterosexual women. Faderman repeatedly claimed that being lesbian was a choice that any woman could make if she was truly committed to women's liberation, and said lesbian-feminists had created their own definition in the 1970s:[99]

Women are lesbians when they are women-identified, they asserted. Never having had the slightest erotic exchange with another woman, one might still be a political lesbian. A lesbian is a woman who makes women prime in her life, who gives her energies and her commitment to other women rather than to men. Some even proclaimed, 'All women are lesbians,' by which they meant that potentially all women have the capacity to love themselves and to love other females, first through their mothers and then through adult relationships.

Lilian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men (1981)

A definition in a satirical lesbian guide book from 1996 returned to the language of personal traits instead of political choices, and incorporated the phrase "romantic orientation":[100]

Lesbian: Named for the Isle of Lesbos, where Sappho, the mother of us all, wrote poetry for cute young Greek girljocks and vied for their affections. Denotes a woman whose sexual and romantic orientation is directed toward women. Some women prefer lesbian to gay because the latter has become so synonymous with men.

Liz Tracey and Sydney Pokorny, So You Want to be a Lesbian? (1996)

COVID-19 pandemic debates

Other definitions of lesbian have been created in online communities and discussed via social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Definitions of lesbian based on the term "non-men", such as the phrase "non-men loving non-men", may have emerged between April and June 2020.[note 8] The concept of non-men (meaning "anyone who is not a man") has a problematic history. The term is regarded by its proponents as more inclusive of non-binary and trans people who are not men; however, it positions them as the "other" in relation to men as the norm. The term maintains that norm by defining other people as a negation of being a man and recentering men, particularly straight, white, cisgender men.[103] Historically, lesbian women have been regarded as not "real women" ("nonwomen") and gay men as not "real men" ("nonmen") compared to heterosexuals.[104] The nonmen/nonwomen concepts also have a history in antiblack racism, which views black people as if they are nonhuman compared to white people.[105]

On July 4, 2021, the LGBTA Wiki introduced its own definition of lesbianism as "queer attraction to women" and framed common lesbian definitions as being exclusionist, invalidating, and harmful.[106] A blog post further explained the reasoning behind the administrators' new definition and alleged that terms used by its critics and in other definitions (such as lesbians being women, gay women, women only attracted to women, women not attracted to men, woman-aligned, feminine-aligned, or femspec) were TERF rhetoric.[107] Multiple administrators were sent threatening and abusive messages; as a result, the article was locked against further edits and the comments feature was disabled.[108]

The phrase "queer attraction" has a mixed history of use. On February 21, 1929, The Well of Loneliness was disparaged as an obscene book with a tendency to debauch public morals; City Magistrate Judge Hyman Bushel's judicial opinion condemned "the queer attraction of the child to the maid in the household".[109] In a more neutral sense, the phrase has described things that the local gay community is attracted to, such as an establishment in a gay neighborhood having a queer attraction for the community,[110] and possible same-sex attractions in queer readings of films.[111][112] Other uses have included a strange or unusual attraction that draws some types of people together (such as rogues and vagabonds),[113] incestuous attraction (such as a nephew to his aunt),[114] the sexual interest that men stationed at military bases may take in local girls,[115] and the way a person and an object are drawn to each other (such as a joke from a student periodical in which "a boy and a pie, left alone together, are found to have a queer attraction for each other").[116]

Perceptions and discrimination

Health care

In the United States, lesbians face significant disparities in health care. Providers often lack adequate education about specific needs of LGBTQIA+ populations and may hold homophobic beliefs or make heteronormative assumptions. Compared to straight women, lesbians are less likely to seek gynecological care for prenatal care or family planning; however, gynecological care includes screenings for cervical and breast cancer and testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Lower rates of accessing gynecological care may be related to cancers and STDs remaining undetected and untreated. Financial barriers such as lack of health insurance also impact health care access.[117]

Stereotyping

Gender expression is a separate concept from sexual orientation, so various traits that are considered feminine, masculine, or otherwise are not indicative of a lesbian identity. Lesbians are often stereotyped as having "masculine" appearances and interests. Lesbians are not automatically masculine,[118] but some choose to express themselves in such a way. Butch lesbians, for example, are a popular subgroup of masculine presenting lesbians.[34]

Media

- Main article: Lesbians in media

Resources

- Autostraddle — Digital magazine for lesbian culture

- Eurocentralasian Lesbian* Community (EL*C)

- Lesbian Herstory Archives

- National Center for Lesbian Rights — Legal resources and assistance (U.S.)

- Sappho for Kolkata — Activism for lesbian, bisexual woman, and transman rights (Eastern India)

Notes

|

References

|